There’s a famous story about the band that continued to play as the Titanic sank. Led by violinist Hartley Wallace, the 8-person cast played and played as the ship submerged, switching from initially cheerful tunes towards increasingly somber music, finishing – allegedly – with a rendition of “Nearer, My God, to Thee”, an old Christian hymn. All eight musicians would drown in the ice-cold waters.

A somewhat similar series of events seem to be taking place in Paris these days, only the resilient performers are members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting, and the sinking ship an 800-page tax treaty with structural issues and far too few lifeboats.

“The show must go on” is the showbusiness mantra; in the tax world, they just say “the publication of the convention moves the international community a step closer towards finalisation of the Two-Pillar Solution to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation and globalisation of the economy.”

A long and troubled voyage

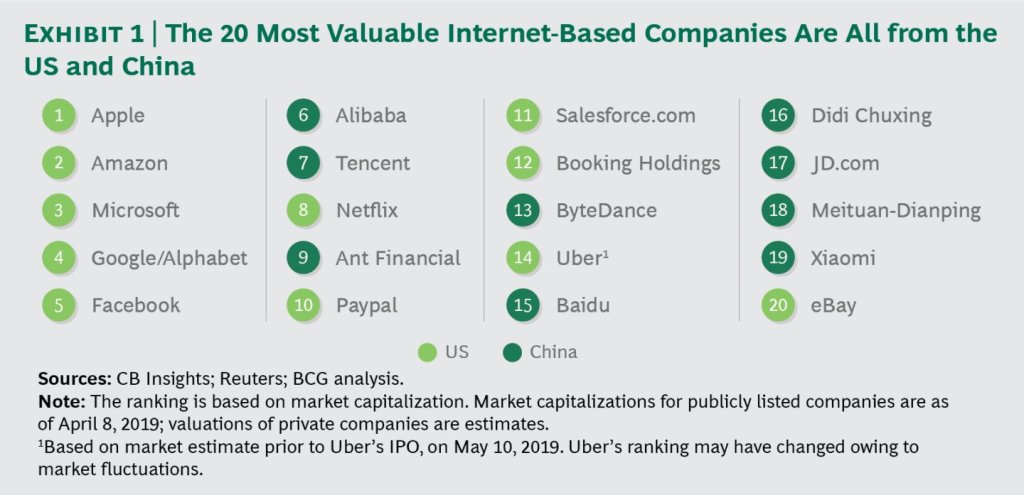

The crux of the problem that the fine folks congregated in Paris are trying to solve is this: Europe1 wants a larger share of the tax pie from Big Tech – the Apples, the Facebooks, the Googles of the world; they have a lot of customers in Europe, after all. But the United States doesn’t like that very much; they believe it’s their pie entirely as the companies are resident there2.

That’s the simple version of the saga that’s been going on since 2013, which has fractured transatlantic tax relations, and which is situated in a broader story of globalization, digital business and tech war.

But the political dynamic is unmistakeable. After a decade of discussions, we’re stuck in an endless doomloop of escalation, resolution, delay, and back. And not much closer to agreeing how to tax the digital giants.

First, escalation. It was the French who initially promoted “tax challenges arising from digitalisation” onto the global tax agenda at the OECD, the world’s de facto global tax organization, in 2013. To stress its importance, the French made sure that digital taxation was the first of 13 “action points” in the high-profile OECD/G20 ‘Base Erosion and Profit Shifting‘ project.

Then, resolution. After two years of discussions, the parties simply concluded in 2015 that it would be “impossible to ring-fence the digital economy from the rest of the economy for tax purposes”. That suited the Americans: “you can’t target our Big Tech firms”.

Then, delay. Further work was parked in the OECD’s “Task Force on the Digital Economy”, in 2017 given a mandate to carry out a three-year information-gathering exercise and produce a series of recommendations by late-2020.

That didn’t placate many, and certainly not the French. They went back to escalation, aggressively calling for new – and quick – solutions in 2018, this time under the OECD/G20’s so-called “Two Pillar” project. They also pushed for the European Union to collectively adopt a “Digital Services Tax” (DST), which would impose a 3% levy on revenues from digital services, primarily hitting US companies like Google, Facebook and Amazon. And the French adopted their own domestic DST too, alongside a host of other countries – now totalling around 40 – who pursued similar national rules.

The Trump administration, as expected and perhaps justifiably so, wasn’t happy. Starting in 2019, the US Trade Representative launched waves of section 301 investigations against countries implementing taxes targeted at Big Tech, threatening retaliatory trade sanctions.

Escalation of conflict brought countries back to the negotiating table at the OECD, with renewed momentum as President Biden and his Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in 2021 worked with partners to find a resolution that widened the scope, so that the so-called Pillar One (of the Two-Pillar project) would target not just big tech, but big, profitable firms in general. From manufacturing to software, they would all have to pay more of their taxes in countries where they make their sales. Europe (and everyone else) agreed to delay or pause their digital services taxes, while the US withdrew tariff threats.

Now, two years later, and not much has happened. In July this year, 138 countries signed a statement recognizing further delay on negotiations, further delay on resolution, and further delay on digital services taxes. 138 was less than the 143 members of the discussions though. Prominently, Canada was among the holdouts, refusing to sign the statement. Minister of Finance Chrystia Freeland laid out her reasoning clearly:

Two years ago, we agreed to pause the implementation of our own Digital Services Tax (DST), in order to give time and space for negotiations on Pillar One. But we were clear that Canada would need to move forward with our own DST as of January 1, 2024, if the treaty to implement Pillar One has not come into force.

Chrystia Freeland

Against the tide

It’s not that the fine folks at the OECD and the Inclusive Framework have been sitting on their hands, of course. There’s been programmes of work, blueprints and model rules, economic impact assessments, publications and consultations, statements and progress reports, building blocks and meetings and meetings and meetings.

Just last week, they released the preliminary text of the Pillar One (Amount A) treaty, a monster of a multilateral convention that would effectuate the reallocation of taxing rights covering $200bn in corporate profits, giving France and all its companions – finally, formally, and with US approval – the right to get a bigger share of the Big Tech tax pie.

(And if you manage to comb through the 800 pages of incredibly dense, technical, highly complex treaty text and explanatory statements, I guarantee you will feel “Nearer, My God, To Thee” indeed.)

No, the problem is simply, that the whole thing probably won’t ever materialize. Politically speaking, it might just be akin to rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

I’m not saying that the underlying ideas won’t prevail. Certainly, there’s an inescapable appetite for more “market-based taxation”, the allocation of taxing rights to the places where companies sell their goods and services, at the expense of countries where companies are headquartered. Debate on international tax reform is thoroughly occupied with market-based taxation these days.

But its specific manifestation in a great multilateral convention, which requires the United States’ legislative branch to formally ratify a clear and overt transfer of taxing rights from the US to foreign nations – that seems unlikely to happen.

Biden’s Treasury Department is doing all they can. Janet Yellen has argued that the treaty will, in fact, be “largely revenue neutral for the United States”. That’s not entirely far-fetched. Despite around 50% of the companies in scope of the agreement and the majority of profits to be reallocated currently residing with the US, the negotiated expansion of the scope means some independent estimates find upside in the agreement for US revenues.

But of course the agreement will inevitably entail some give-away of US taxing rights. And certainly a disproportionate targeting of US companies. That focus matters, as does the gross revenue losses. And as such, there is wide bipartisan agreement in Congress on US resistance to new foreign taxes on Big Tech, in all shapes and forms. It’s a difficult sell to the domestic crowd for Joe and Janet. Already, just a few months after the July ceasefire, Yellen has admitted that the US will not be able to meet the 2023 deadlines for the process to move forward in a timely manner.

And everyone seems to act accordingly. The OECD won’t speculate, of course. As the Paris-based organisation’s tax chief, Manal Corwin, told the Financial Times in July: “There’s been a lot of discussion and speculation about the prospects of ratification in the US. But that is the third milestone [after finalisation of text and signing by countries] and our approach and our view is we need to get to the first two for that last one to be relevant”.

But Canada’s boldness, its reluctance to continue the charade, indicates a broader belief that the probability of multilateral resolution is low, so why not move forward with domestic rules instead? Informally querying the World’s Finest Tax Followers(TM) in a Highly Scientific Poll(TM), I found that most observers believe there’s no more than a 25% chance the Pillar One treaty is ever realized.

So what does this mean for the future? Where are the lifeboats?

The immediate consequences of continued delay and failure to finalize the treaty will, inevitably, be a return to the doomloop, with escalation through digital services taxes and its variations (under miscellaneous guises such as ‘significant economic presence’ rules or ‘equilization levies’ or digital witholding taxes or digital permanent establishment rules, etc.), such as that pursued by Canada.

And the response will be more US saber-rattling. Already, both sides of the US Senate are calling on the US Trade Representative to “make clear that your office will immediately respond using available trade tools upon Canada’s enactment of any DST”. A threatened freeze on maple syrup imports is just around the corner.

If a full-blown global trade war breaks out, it’s bad news for everyone. The OECD estimate such a scenario could drag down global GDP by around 1%. No one wants that.

Because of these risks – US retaliation and global trade war – some observers are puzzled by Canada’s decision to go ahead with a digital service tax. One former OECD tax division head called it “a mystery (…) why the government of Canada has broken ranks with other major players in the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting—by announcing its intention to proceed unilaterally with a digital services tax.”

But there’s really nothing puzzling about Canada’s move, or the proliferation of digital taxes globally. International corporate tax policy has risen to the top of national and global political agendas, with governments individually and collectively asserting their authority against the forces of globalization – a significant shift from years past. Policy-makers like Chrystia Freeland are under pressure to act, and many strategically profile themselves as leaders who will crack down on digital giants. They can’t wait around forever; too much political capital is invested in the Big Tech tax agenda.

Moreover, strategically speaking, Canada’s enactment of a digital services tax, and other countries doing similar, could be the very thing that gets us out of the doomloop. Looking back over the last decade, the most significant multilateral developments on digital taxation have come from groups of countries – the EU, prominently, but also emerging markets like India, and developing country coalitions – exerting pressure on the United States.

Indeed, Wouter Lips has analyzed how the EU’s push for digital services taxes “increased the threat of uncoordinated unilateral measures. This created a period of uncertainty and pressured laggard states (read: the US), which helped lead to a tentative window for reform”. Alongside colleagues, my own research has also shown how developing countries are increasingly forceful in pushing global tax discussions in directions that go against US interests.

More and more, US leaders are fighting ‘rearguard’ battles to pare back other countries’ attempts at expanding their taxing rights at the expense of US revenue, as Lukas Hakelberg discusses. Clearly, unsticking the bogged-down discussions and reconfiguring the whole project to look less anti-American was a prime objective for Biden as he took office.

Sink or swim

The optimistic view, then, if we’re looking for lifeboats, is that the mounting threat of aggressive global trade wars over digital taxation will raise the stakes – a sort of ‘rational deterrence’, a tax-specific manifestation of the ‘mutually assured destruction’ (MAD) doctrine.

That could bring the US – including bipartisan Congress – and partners together to produce a sustainable outcome. The US will want to avoid a proliferation of digital services taxes and the effective transfer of tax revenues away from home, while everyone else will want to escape punitive tariffs and worsening multilateral relations.

It’s also worth noting that China is largely aligned with the US on these matters: As the biggest digital trader in the world, they certainly don’t like the prospect of more foreign taxes on Baidu, Tencent and Alibaba.

But of course a stable settlement is not given. There’s every chance we’ll be stuck on the doomloop for a while yet, with further escalation, resolution, and delay, until eventually the whole project finally either sinks or swims. While we wait to find out, the band will surely just keep playing and playing and playing and playing…