Let me start by saying – and I suppose this is quite the understatement – that there are more important things happening in the world right now than what I’m going to write about in this blog. If you look up and out even just a little bit then, well… yeah. I am almost embarrassed to be writing yet another piece about the global minimum tax rather than, you know, more urgent matters. Yet here we are; this is what I know, and hopefully, I’ll persuade you that this focus is not without reason.

And that is because the point I want to make in this post is that the global minimum tax has the looks of a raging, god-damn, full-on, absolutely smashing success.

Now, success is of course a relative term. And heaven knows there will be people lining up to disagree with me. Business will say the compliance costs are too high and outweigh the benefits, lawyers that it violates existing tax treaties or international law, NGOs that the ambitions are too low and the benefits unduly skewed, Republicans that it discriminates against US firms, competitiveness fetishists that it constricts growth, the Heritage Foundation that it violates national sovereignty, philosophers that it doesn’t truly end the ‘race to the bottom’ but only shifts it, and so forth. They might all have a point.

What the global minimum tax does do, however – and this is my benchmark for success here – is effectively put a stop to tax competition. That’s what it looks like so far, anyway. Why is this a worthwhile benchmark for success? Well, because it is rather fucking revolutionary. You couldn’t have lined up a single tuned-in person 10 years ago who would have predicted that such an achievement would be possible. None. You would have been laughed out of the room. Corporate income tax rates have been falling – everywhere around the world – for half a century. Consistently. Like clockwork. The reasons, structural and enduring, are abundantly clear: In a world of sovereign taxing nation-states and globally integrated economies and markets, governments will continually lower local tax costs for mobile capital to attract investments and profits. The theoretical solution is equally clear – strongly enforced, expansive, multilateral cooperation – but was broadly seen as practically impossible given the highly uneven distribution of costs, benefits, and incentives for states, as well as the nature and governance of tax policy itself.

With the stroke of a pen, all of that has been undone. (I’m simplifying.) To be fair, the global minimum tax was only just agreed. There was a high-level commitment from about 140 states in 2021, and it only starts taking effect in 2024. Thus, evaluations will inevitably be somewhat premature, especially considering that the whole thing might be hanging by a thread because of an angry Orange Man – although I am less pessimistic than others on this matter.

But there are signs. Signs, I’m telling you. Let us review.

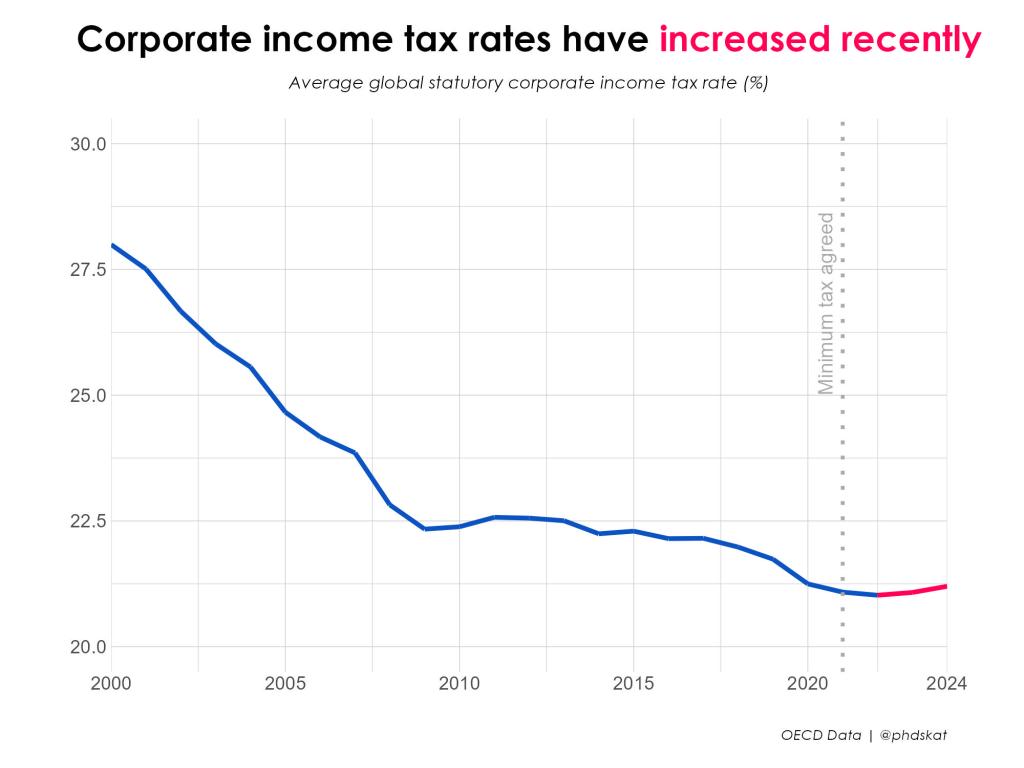

First, there is this: After half a century in free fall, the average global statutory corporate income tax rate has increased since 2022. It has increased only slightly, inching upwards, but that represents a stark break with a long historical trend.

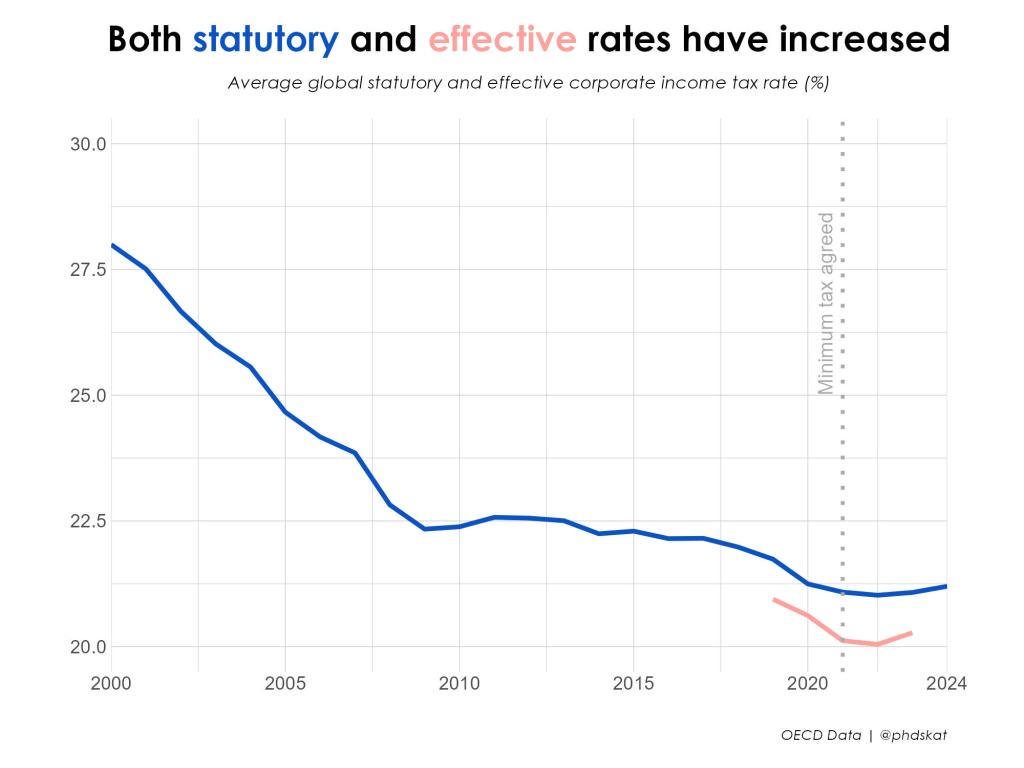

Of course, every business knows that what really matters is not the statutory (headline) rate but rather the effective corporate tax rate, which takes into account tax base carve-outs and exemptions and credits and so on. Here, because of difficulties of measurement, available data is less consistent, but the OECD has published a comparative time series in the last few years. And when we look here, we see that average effective corporate tax rates have increased too. Even more so than statutory rates, in fact. Usually, it’s the other way around (statutory rates have historically fallen faster than effective rates because governments have combined rate cuts with tax base broadening). This suggests that policy-makers are now both raising headline rates and tightening the tax base.

We’ll see if the trend holds in the coming years. There are some reasons to be skeptical. These are, as noted, short-term developments, and things can change quickly. Geopolitical changes, say the Orange Man, might help re-ignite the race to the bottom, reversing the trend again.

For instance, there was a similar, but only temporary, increase in statutory corporate tax rates around the world in the wake of the 07-08 global financial crisis (GFC). However, there was no corresponding rise in effective rates between 2009 and 2012, at least in the OECD+ countries; effective rates still dropped. (And that’s measured following the same methodology – Devereux-Griffith, for you freaks – as the recent OECD data series, which is noteworthy given the extreme variation in effective tax rate calculation approaches out there.) This would align with the two-level game played by (OECD) governments in the post-GFC years, squaring the circle between popular uproar and tax competition by adopting “incremental and symbolic, but largely ineffective, reforms”. But this is not what we see now; today, governments are adopting symbolic and effective reforms.

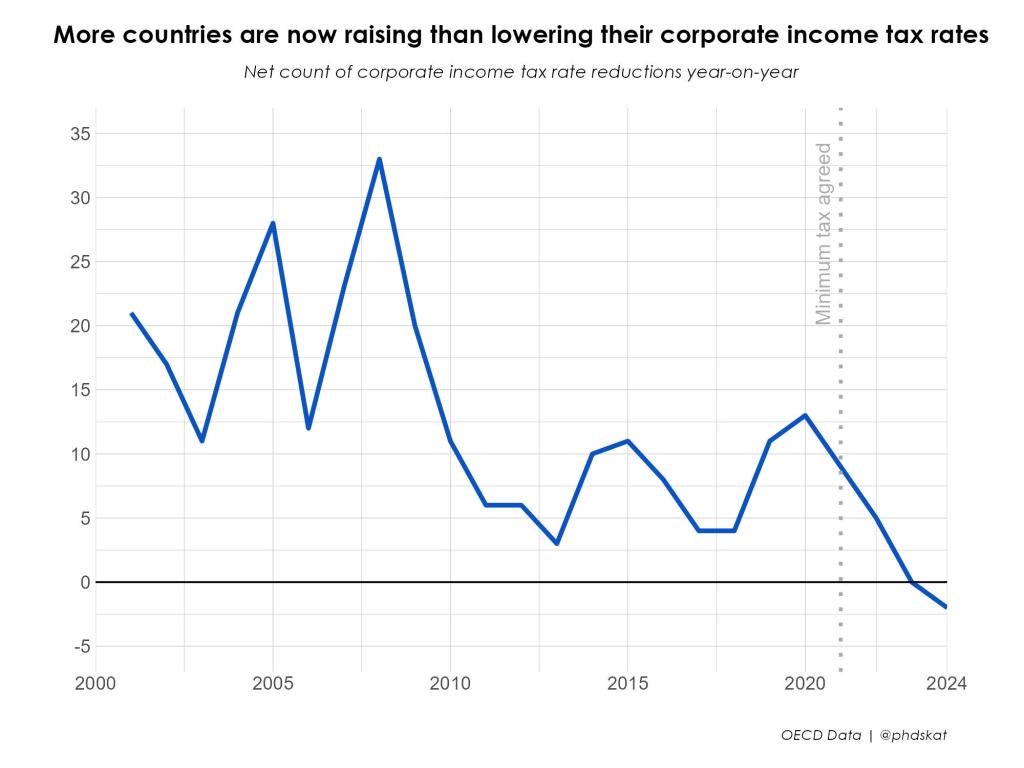

Moreover, while the average statutory corporate income tax rate increased between 2009 and 2011, the net number of countries that lowered their rates each year was positive. Many governments continued, even in the post-GFC years, to engage in tax competition, but they only lowered their tax rates a little. Meanwhile a few others, likely animated in part by the crisis, raised their rates a lot. Thus, we never had a year in which more countries raised than lowered their corporate income tax. That is, until 2024:

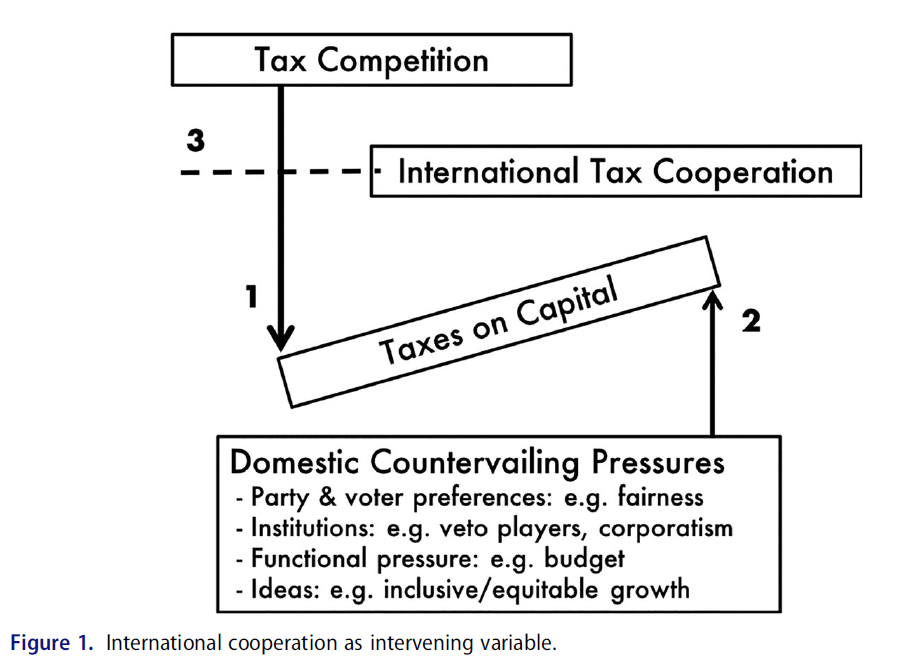

Another point of skepticism might be that recent increases in corporate income tax rates are not specifically a result of the global minimum tax. As with the post-GFC years, the last half-decade has seen large economic crises (COVID, Russia, energy), which – especially in Europe – have unquestionably raised appetites for higher taxes on businesses, especially those seen to be benefiting from the crises, such as financial and energy/fossil fuel firms earning windfall profits. So maybe that’s what is driving the increases, not the global minimum tax? Well, the two logics aren’t mutually exclusive. As Thomas Rixen and Lukas Hakelberg have argued, domestic pressures for increasing taxes on capital are necessary, but not sufficient, to make it happen in the face of tax competition. Effective tax cooperation – of which the global minimum tax is an excellent example – is the enabling variable: It allows governments to pursue progressive tax policy without undue fears of capital flight. So if recent corporate tax rate increases are an effect (in part) of the global minimum tax, this is exactly what we should expect to see: governments more willing and able to pursue political preferences for higher capital taxation.

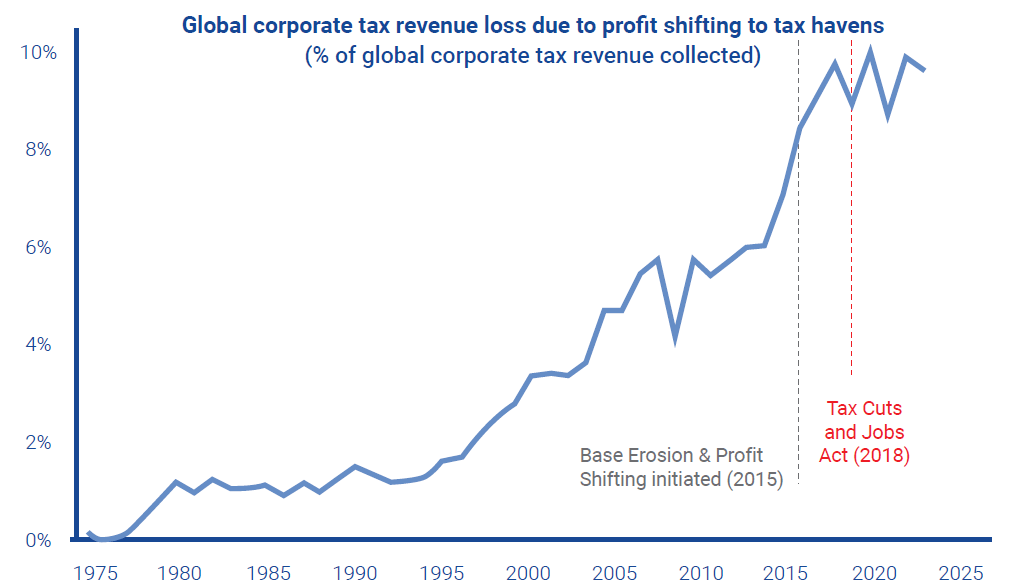

There is another plausible argument that recent changes are not so much down to the global minimum tax but rather other major corporate tax reforms. Could it be the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project? Initiated in 2013 and concluded in 2015, its policy recommendations – including expanded tax transparency, a multilateral instrument for changes to tax treaties, and anti-abuse rules of all kinds – were rolled out over the following years. Or could it be the US Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) from 2017, which forced repatriation of US corporations’ offshore profits, and generally reconfigured the US corporate tax system? These reforms have undoubtedly prompted significant reorganization of global corporate structures; investment flows; IP, risk, and profit locations; etc.

On the one hand, some available evidence would seem to back this theory. Gabriel Zucman and Ludvig Wier’s rolling estimates of the scale of global profit shifting show a post-2015 slowdown in the growth of profit shifting, and an outright post-2017 stabilization. This could certainly indicate that, as Zucman and colleagues have suggested, “absent these policies, profit shifting may have been even higher today”.

On the other hand, when we look at the 2015-2021 period on the first three graphs above, it’s hard to see any discernible slowdown in the race to the bottom. So, if the risk of corporate capital flight truly flattened in these years, policy-makers simply did not react to it, which runs counter to what we would expect. It seems more likely that BEPS and TCJA had some effect, but nothing like the global minimum tax. That would align with what most informed assessments of the BEPS/TCJA era regulations have found, namely that while they are a leap forward in terms of combatting global profit shifting, they did not get at the heart of the problem. In a recent paper, I summarize the existing research as such:

“Attempts at cracking down on corporate tax avoidance by OECD countries in the last decade, principally under the flagship ‘Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ (BEPS) project, have focused on minor adjustments to century-old values while putting little credible threat of pressure behind their efforts. (..) The result has [been] limited change to the tax planning opportunities afforded by the global tax system”

In contrast, the global minimum tax does get at the heart of the problem. It includes a strong, expansive enforcement mechanism, an “insane super-charged extraterritorial taxing power” (which is incidentally why (some) US politicians dislike it so much). It completely reconfigures international tax politics and its conventional problem structure. It is expected to raise in the range of $200bn annually in additional global tax revenues, which would amount to an unprecedented 10% increase in the world corporate income tax take.

These design features, and the expected impacts, are why nascent trends indicating an end to the race to the bottom might well have staying power.

Should that be the case, that would have significant economic and political ramifications over the short and long term. The consequences are too many and too complex for a brief review. (Perhaps a theme for another blog.) And they’re entangled with policy developments in other areas; for instance, it is clear already that as the global minimum tax puts bounds on governments’ ability to compete for foreign investments through the corporate tax system, competition will shift towards subsidies, industrial policy, personal income tax incentives, etc.

But one systemic insight, I think, is already worthwhile emphasizing: The global minimum tax illustrates, to paraphrase a preferred Zucman idiom: the race to the bottom is not a law of nature; it is a policy choice. In his 2008 book, Rixen notes that, “tax competition is seen as a natural corollary of economic globalization that is not itself in need of an explanation. It is assumed to be an exogenously given force”. Now, if tax competition as we have known it for half a century, at the hands of the global minimum tax, is no longer a given, that should be a hallmark lesson in the power of weaponized regulation and international cooperation. And that is certainly a lesson worth remembering.