Globalisation and the intensified competition among firms in the global marketplace has had and continues to have many positive effects. However, the fact that tax competition may lead to the proliferation of harmful tax practices and the adverse consequences that result, as discussed here, shows that governments must take measures, including intensifying their international co-operation, to protect their tax bases and to avoid the world-wide reduction in welfare caused by tax-induced distortions in capital and financial flows.

(OECD, 1998. Harmful Tax Competition – An Emerging Global Issue, p.18)

While tax competition had been an interest to academics for decades before, the 1998 OECD report really put ‘tax competition’ on the global political agenda. A substantial literature has followed, but rarely does it touch upon the ethical foundations of tax competition.

A recent book by Peter Dietsch, professor at the Department of Philosophy of the University of Montreal, does just that. ‘Catching Capital: The ethics of tax competition‘ sets out to accomplish three main things: It seeks to investigate the phenomenon of tax competition and its ethical underpinnings, to argue that it is damaging, and to offer a useful solution to the issue.

Given the book was published in almost a year ago, in August 2015, it seems to have received relatively little buzz. As far as I was able to identify, there is only a few available reviews and just a handful of citations and mentions. But perhaps it is too early to judge. Having read the book with interest, I offer my thoughts below, not quite as a pure review but also as a repository for thoughts on the arguments and ideas put forward by Dietsch in the book.

As an introductory summary, I found the book both entertaining in both its specific point of attack (ethics), its substantive arguments and its normative character. Dietsch delves fascinatingly into the political philosophy of taxation, a theme so basic yet so far from modern tax discussions, whilst connecting the philosophical discussions to relevant, important real-world issues. The discussions go deep when the author desires (for instance when dismissing the economic efficiency arguments against tax cooperation) and shallow elsewhere (for instance when discussing current international tax reform streams). The structure, at times, leaves something to be desired – the argument flow within and across chapters can become muddled and in its persistence to immediately address all potential angles and criticisms of the topic at hand, the pace is often disturbed or broken. But all in all, it is a well-argued and thoughtful piece that succintly explains both a burning platform, an interesting future solution, and a roadmap towards addressing tax competition today.

The book is structured around five chapters, which – to give it all away – can be crudely summed up as follows:

1: Tax competition harms fiscal sovereignty.

2: The solution to tax competition is WTO-style international tax law and arbitration based on “do no strategic harm” principles.

3: Tax cooperation is not inefficient in economic models, and even if it were, this would not mean that it is inefficient in the real world.

4: National sovereignty is enhanced by international tax cooperation, not eroded.

5: Compensatory duties are needed for low-income countries that currently win from tax competition in order to smooth a transition to the new system.

Tax competition harms fiscal sovereignty

On the first point, the point made by Dietsch is clear: Tax competition renders national polities unable to tax capital at their choosing, given that it can escape and transform flexibly to avoid the tax grasp of states. Put simply, capital is darn difficult to tax under current national and international tax systems and in today’s world of globalised capital markets. And the effect is damaged national fiscal sovereignty; citizens cannot any longer decide how and how much they want to tax capital – their choices are institutionally limited and some will inevitably be ineffective.

What has become the ‘natural’ consequent conclusion in policy circles is that we should stop trying to tax capital, and instead tax immobile factors (consumption, land and to a lesser extent labour), as my blog on European tax policy plainly shows. Thus, the most popular current streams in addressing tax competition to accept this slipperiness and nudge us to avert the tax gaze elsewhere. Even more radical reform ideas, such as unitary taxation, which are viewed as a means to tax corporations more effectively, are based on formulary apportionment through less mobile factors such as sales and employees.

But it raises the question of whether or not it is really a good idea to just ‘give up’ taxing capital because it is hard? It may create outcomes that are problematic from an ethics or equity viewpoint. As Dietsch writes, the trend to shift taxation from capital to labour, consumption and land has had the effect that “OECD countries have bought fiscal stability in terms of revenue at the cost of a less redistributive system” (p. 48).

“No strategic harm” and an International Tax Organisation

So what are national politicians to do these days? In chapter 2, Dietsch offers his reply: An International Tax Organisation (ITO), modeled on the World Trade Organisation (WTO), with two key principles of global tax justice, enshrined in international law and enforced via arbitration and expert panels:

- The membership prinicple (with a transparency corollary)

- The fiscal policy constraint

The former is simple in wording, but the devil is in the detail. Individuals and corporations should pay tax in the state where they are members, i.e. where they benefit from the services provided by the corresponding tax expenditure (e.g. public services or infrastructure). And in order to make this assessment, states need transparency, i.e. access to information on economic agents’ behaviour and assets across borders.

Hallelujah, on we go. Right? Not quite. What exactly constitutes ‘benefits from’? Is there a certain threshold, in terms of time, resources invested, or other tangible support received? Unfortunately, Dietsch does not offer a sufficient detailing of the practical implementation of the principle. How are we to judge whether and to what extent a person or a company is a member of a state? In this respect, the membership principle is somewhat analogous to the ongoing discussions at the OECD and EU levels on what exactly constitutes “taxing profits where value is created” – a phase repeated so often by international tax policy-makers that it has lost all meaning. The challenge lies in defining membership, as it does in defining value-creation.

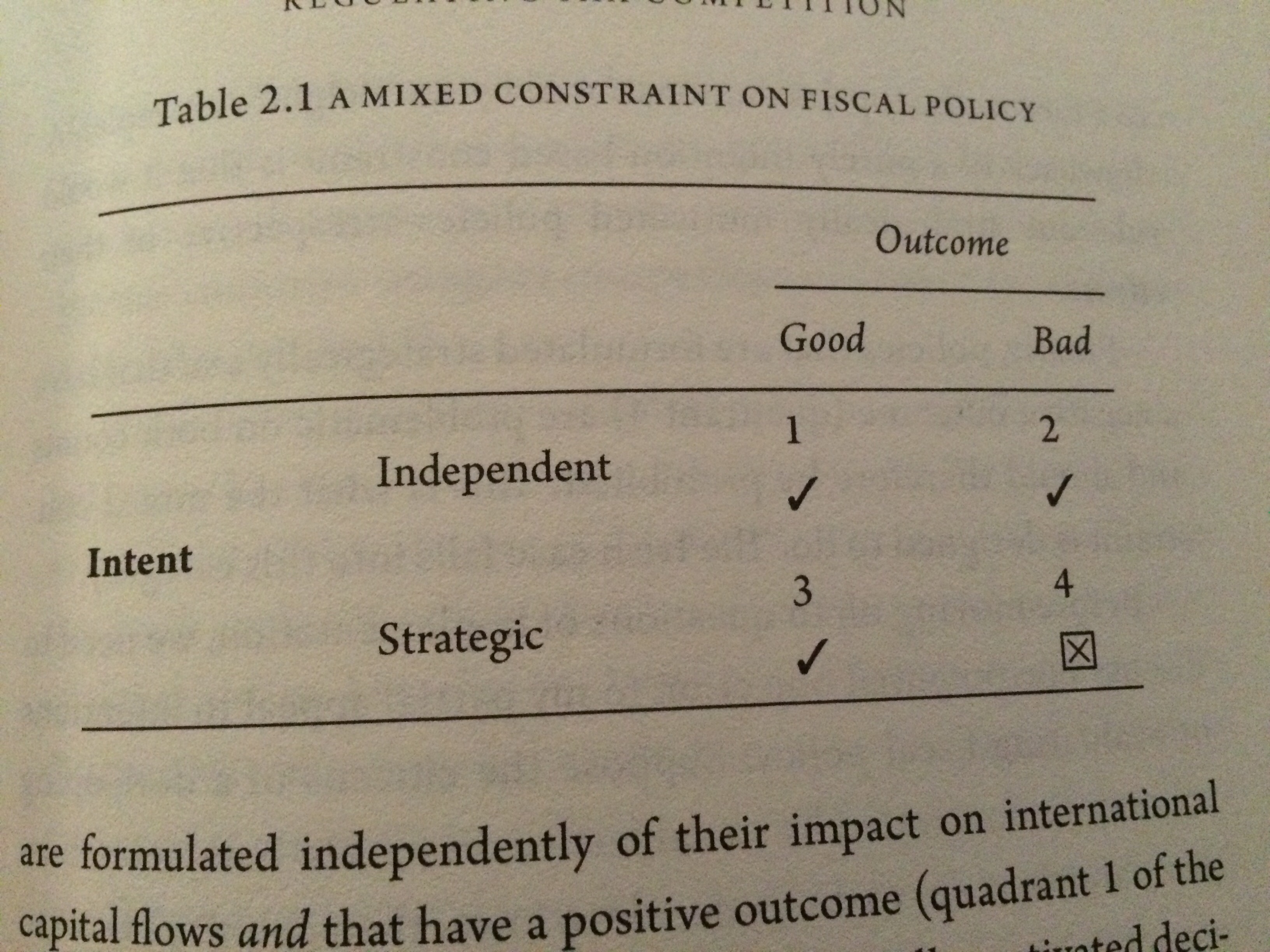

The fiscal policy constraint holds that countries should not engage in tax competition which collectively puts countries worse off. In order to do so, Dietsch holds, tax policies must not:

a) Strategically (deliberately) be designed to attract economic activity from other states, and

b) Negatively affect the aggregate fiscal self-determination of the countries in question

If a national fiscal policy is strategic but non-damaging, it’s okay. This could be where Scandinavian countries invest heavily in free education so as to attract foreign capital. If it is damaging but non-strategic, that’s okay. This could where citizens, say of the US, have exercised their democratic voice to express a preference for relatively low taxes and public spending. If it is both, that’s not okay. Dietsch cites the Irish tax regime as an example here.

The main ideational and theoretical novelty in Dietsch’s proposals here is these principles. The question of a World Tax Organisation has been discussed for decades. But Dietsch’s ethics-oriented inquiry has produced two key principles that are open to challenge but coherent and useful in assessing what is and what is not ‘acceptable’ tax competition. Indeed, Dietsch himself notes that the key challenge of his book is to “identify where the boundaries of the fiscal autonomy prerogative should lie, and what institutions serve to protect them”. But whereas most proposals to address this question, including those surveyed by Dietsch in the book (capital controls and unitary taxation), offer technical solutions to regulating capital (or abstaining from it), Dietsch’s solution is fundamentally different. It is philosophical and principles-based.

The above is not to dismiss his contribution on the enforcement-side. Dietsch usefully substantiates the case for sovereignty-pooling, which is a key prerequisite for most effective enforcement proposals. (I’ll discuss this further when addressing chapter four, which concerns sovereignty.)

On the other hand, the high-level nature of his solutions also means certain technical details are unaddressed. Though the author does touch upon these points, it never becomes quite clear how the membership principle is to be determined, how the intentions and outcomes of national fiscal policies are to be evaluated, or how exactly to avoid all the pitfalls of ITO’s inspiration, the WTO (for instance the continued geopolitical features of its decisions and its rules).

Now, the effect of Dietsch’s proposals, if carried out, are not to be understated. He characterises three types of tax competition, of which the two former are the most problematic and harmful: Competition for portfolio capital, for paper profits and real FDI. These are, to some extent substitutive. As long as businesses can shift paper profits, there is less need to reallocate real FDI. The effect of decreasing competition, in particular of the two first types, will be to produce a more real and true market and economic competition for actual investment and actual economic activity. This is a similar argument we often hear about other proposed solutions, such as unitary taxation and the EU CCCTB – that in limiting ‘backdoor’ tax competition (or poaching), “real” competition would intensify. And that is most likely correct. But as Dietsch details, open, real and fair competition should be preferred – even though it creates other issues – to hidden, on-paper and selective competition. One reason is that the former follows the membership principle, so that when income or assets are shifted between countries, it will align with the location where benefits are obtained from the expenditures of taxes paid.

Tax cooperation is not inefficient

Having outlined the burning platform and the solution, Dietsch needs to defend his proposals. There is no shortage of economic and legal analysis to counter-argue his case. Meeting the former head on, Dietsch adds to his analysis on tax competition as damaging fiscal sovereignty in a philosophical sense, with the point that tax cooperation is not inefficient from an economic point of view. Note that Dietsch’s focus is not on ambitious arguments that tax cooperation is efficient or that tax competition is inefficient per se. He sets out to demonstrate the more moderate claim that tax cooperation, of the sort he advocates, is not economically inefficient.

I was happy to see Dietsch open this argument with an important point, which often gets lost in popular tax debates: Tax is only one side of the fiscal coin. The other side is public spending. In standard economics, taxation is often a bad thing, because the corresponding expenditure is assumed not to outweigh the welfare loss created by the the tax. But Dietsch argues that this general assumption is importantly flawed. Tax provides basic market-enabling (legal frameworks, health and safety, etc.) services and public goods, along with investments in education, health, infrastructure, etc. – all of which may outweigh deadweight losses. Similarly, arguments that tax competition is efficient because it leads to economic growth often rely on assumptions that markets are perfectly competitive and that resulting economic growth will lead to welfare gains that outweigh the corresponding losses. Dietsch finds this to be unrealistic and improbable, in particular at the global level, not least because of the presence of public goods and negative spillover effects. (It may lead to national gains at the expense of neighbouring countries, but this is a lesser argument as it guarantees a race to the bottom.)

One of the key points in Dietsch’s dismissal of tax cooperation as economically inefficient concerns optimal tax theory. Proponents of tax competition that leverage optimal tax theory hold that lowering taxes will result in increased labour supply and decrease tax evasion and avoidance. Analytically, the consequence is less need for tax cooperation to stem a race to the bottom of capital taxation. And this may be empirically true today. But these elasticies (the extent to which the labour supply and evasion/avoidance change with tax rate changes) are (partly) institutionally determined, and thus Dietsch argues there is no reason to assume today’s elasticities for tomorrow – they can be modified through policies and thus we can change the factors in the optimal tax calculation. For instance, by introducing stronger international cooperation on capital tax evasion, it is possible limit the tax evasion elasticity, and thus make tax systems more progressive by increasing the optimal levels of capital taxation, shifting the tax burden back on to mobile capital factors.

The upshot of Dietsch’s line of argumentation is two-fold. Firstly, because the assumptions underlying economic pro-tax competition models assume away key institutional features and fail to capture real life features adequately, they tend to prescribe levels of capital taxation that are below the optimum. Secondly, because these standards models are insufficient, Dietch calls for better empirical research on whether specific tax policies represent aggregate (Pareto) improvements or deteriorations of welfare, rather than whether tax competition in general is good or bad. On these points, it is fair to question whether Dietsch’s assessment of economic theory and research is somewhat stylised. The economic literature on tax competition is diverse and comes to conclucions all along the spectrum, as Dietsch also recognises. Yet his dismissal of this literature rests mostly on general traits and models, which may be dominant in the literature, but which do not paint the full picture.

Tax cooperation enhances, not erodes, national sovereignty

The second key defense that Dietsch makes for his proposals is that tax cooperation does not undermine national sovereignty. Traditionally, this has been the main argument against international tax cooperation. Countries want to retain full rights over taxation, often viewed as a cornerstone of the sovereign nation-state and a key part of the social contract. More than anything else, this is why we do not have international cooperation on tax to the same extent we have it on trade or human rights.

But the trade-off between cooperation and sovereignty, and the notion of sovereignty which this perception of a trade-off implies, is inadequate in today’s world, argues Dietsch. The choice today is to maintain full authority, based on the outdated Westphalian concept of sovereignty, remaining unable to tax capital effectively, or to pool some sovereignty for effective capital taxation, thus reinforcing sovereignty itself.

While Westphalian sovereignty – the agreement on non-intervention in a states’ internal affairs by other states, named after the 1648 Peace of Westphalia – may have been a useful framework for fiscal policies in a world of immobile production factors, it falls short in a globalised world. The fundamental mismatch between internationally mobile capital and territorially-bound states cannot be ignored.

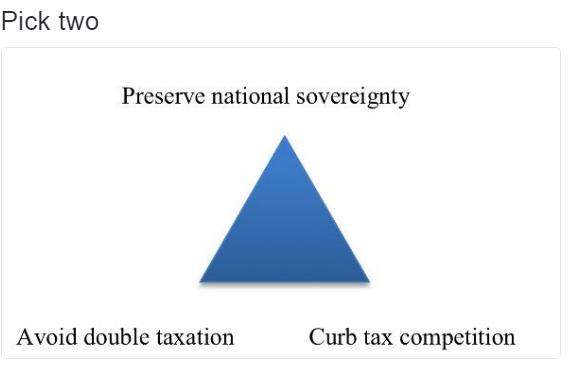

As Dietsch’s colleagues, Thomas Rixen and Philipp Genschel have detailed, any individual country faces a trilemma in addressing tax competition. It can only curb tax competition by relaxing sovereignty or unilaterally engaging in double taxation.

The international tax system of today is based on the historical choice to pick national sovereignty and avoiding double taxation, as countries avoid real international cooperation and emphasise the avoidance of double taxation through bilateral tax treaties.

One of the most important interventions of this book is to remind us that national sovereignty is not absolute. Just like with individual personal freedom, the authority of an individual country will always, at some point, impact the authority of another. The myth of absolute freedom or absolutely sovereignty is just that – a myth.

Here, Dietsch latches on to recent developments in international law and argues that sovereignty needs to be re-cast as a responsibility rather than a right. This means it comes with caveats, of which Dietsch in particular highlights the requirement to respect the fiscal self-determination of other states. If we accept this argument, that sovereignty is a responsibility, the act of tax cooperation becomes in fact not a violation or sovereignty but a central feature of it.

This is an idea becoming increasingly loud. As recent as July 10, Harvard professor Lawrence Summers launched a call for “responsible nationalism” in the Washington Post. His words align well with Dietsch’s analysis:

What is needed is a responsible nationalism — an approach where it is understood that countries are expected to pursue their citizens’ economic welfare as a primary objective but where their ability to damage the interests of citizens of other countries is circumscribed.

Unfortunately for Dietsch and Summers, this is also an idea that is unlikely to take hold just yet. Whether based on a correct analysis or not, national self-determination remains the ultimate backstop to international cooperation (in particular on tax) in the eyes of national policy-makers.

Transitional justice

Before rounding off, Dietsch explores a number of subsidiary ethical questions related to the implementation of his proposals. Should small developing countries be allowed to continue tax competition? How should we calculate compensatory duties (Dietsch’s proposal for sanctions under the new ITO regime)? And what about the populations of existing tax havens? While these are interesting explorations, the book skips quickly across the topics, which leads us to conclude they are included largely for the sake of mention. The limited analyses, e.g. on calculation of tax losses from competition (an extremely difficult topic in itself), also means this is the weakest part of the book.

A diligent, normative, and also non-normative book

In conclusion, it is worth highlighting that Dietsch’s book is a normative one. It argues that tax competition is significant and damaging, and it proposes a real solution to deal with this problem. But then again it also deliberately avoids, somewhat awkwardly, being normative. In fact, the author is extremely careful to emphasise what he is and is not making claims about. Dietsch notes, for instance, that income inequalities within and between countries are exacerbated by tax competition, but makes no definitive claims as to whether this is good or bad. At times, the author provides almost all the arguments necessary to make further normative claims, but avoids going all the way, perhaps for fear of over-stretching or because he finds their solutions immediately unfeasible or out of scope. This is, in a sense, admirable integrity, but also to some extent disappointing.

In avoiding some of those conclusions, I think a lot is missed. I applaud Dietsch for his diligence in bringing his arguments, again and again, back to questions of ethics. To my mind, most of the key questions we discuss today on tax issues always somehow trace back to questions of morality. (For Dietsch, of course, this question of ethics is not about individual agents but rather the ethics behind the design of institutional system to deal with tax and tax competition – another debatable omission.) Unfortunately, Dietsch often avoids actually making any substantive claims regarding ethics, beyond those concerned with national fiscal sovereignty. For instance, Dietsch’s book is adamant that tax competition is really only a problem for the sovereignty of large states (because small states benefit from it), and the solution should come from these countries. If the book finalised its lines of argument that tax competition worsens inequality (which may hurt the economy too), that it increases risk of and exacerbates financial crises, that it distorts fair market competition, and so forth – in addition to the substantiated claim that it undermines sovereignty – he might have come to the conclusion that it is not only detrimental to large states, and that is a problem more wide in scope than sovereignty.

On the other hand, the deliberate lack of normativity is also a strength at times. Dietsch proposes no subjective theory of ‘fairness’ or ‘justice’, nor any opinion on the ‘right’ levels or balance of taxation and similar questions, and he develops principles and recommendations that are applicable largely without reference to national or international politics or tax systems. In this way, he leaves the utilisation of his arguments open to a range of actors and groups with varying interests.

Because of the authors diligence, while there are and will continue to be prominent counter-arguments to the ideas advanced by Dietsch in this book, the book has already surveyed and responded to many of the most obvious ones, at every turn of the argument, though with varying conviction and success. But even if one only buys halfway into the proposals put forth, accepting some of the ideas as relevant, this is an important stepping stone. As Dietsch, citing Pablo Gilabert, notes:

.. If the institutional reforms laid out in part I turn out to be unfeasible for political reasons today, there still are a number of things we can and should do to make their implementation possible in the future.

5 responses to “Catching Capital: Thoughts on Dietsch and tax competition”

[…] behavioural effects are treated as exogenous (i.e. “this is how the world is”). As my review of Peter Dietsch’s recent book on tax competition […]

[…] structure, and probably greater overall coherence. And compared to Dietsch’s previous Cathing Capital, as a compilation it is much more diverse and yet more detailed, though the reading flow […]

[…] In the same way that international tax competition de facto undermines national sovereignty (effectively constraining national policy choices), while de jure leaving it untouched (nations formally retain the right to design policy), we might say that BEPS de facto is a pooling of sovereignty, although de jure it is not. National sovereignty has effectively been pooled or surrendered as a result of the BEPS process. […]

[…] more harmful to other countries than others. (On that, I lean towards Peter Dietsch’s ethical discussion of tax competition). The work is definitely cut out for researchers, practitioners and other […]

[…] policy-making away from the OECD. From early work by Vito Tanzi, former tax chief at the IMF, to Dietsch, Rixen, Avi-Yonah and others, calls for a truly global tax organisation – far from the […]