The European Union is a major player in international tax politics. Alongside the OECD, the EU has arguably been the most significant actor in redesigning international as well as national tax rules and norms over the past decade.

So it matters what the EU’s institutions and its Member States are doing and saying on tax policy. It gives us a glimpse at the current status as well as the future of international and national tax policies, certainly within the Union but also beyond, as European norms spread throughout the world.

Luckily for interested observers (like me), the EU is very open about its tax policy work and its favoured tools and approach – which makes it accessible and analysable.

Since 2011, the European Commission (EC) has published an annual analysis of Member States’ economic and social policies, along with a set of policy recommendations, called country-specific recommendations (CSRs). Included in the CSRs are proposals on tax policies. In fact, there are many tax policy recommendations. Over the past five years, it comes to around 250 by my count, with an average of 20 Member States receiving tax policy proposals each year.

I mapped and categorised each country-specific EU tax policy recommendation over the past five years, based on of their tax policy subject and the specific recommendation given.

What does this tell us about EU tax policies and politics of European taxation? Quite a lot, in fact. Firstly, the recommendations show us the current paradigms within economic and tax policies at the international level. The EC tax-related CSRs are not random ideas for countries’ tax systems cooked up by European bureaucrats. Where recommendations are perceived as needed, it is largely because national tax systems deviate from an understood, accepted norm of ‘best practice’. For instance, the “broad base, low rates” mantra in taxation has long been a favourite of the OECD and the European Commission, which, as we shall see, shines through in the tax policy recommendations.

Secondly, the analysis tells us something about the political economy of tax policy within the EU. The number and nature of CSRs to Member States reveal patterns of national deviation from international tax policy paradigms, but it also shows us intra-EU politics – what can be said about which countries, and which topics can we recommend on? The fact that France (themes: need to simplify tax system and reduce inefficient tax expenditures) and Germany (improve tax admin. services and reduce tax on labour) received more than 15 tax policy recommendations whilst the UK received just four probably does not fairly reflect the volume of issues with those national tax systems – but from an EC perspective, it made sense. Similarly, the fact that recommendations to reduce the tax gap are almost always directed at the Eastern block (Belgium was the only Western/Northern EU Member to receive such a CSR) probably neglects the tax evasion issues faced by Europe’s largest economies – but as seen from Brussels, the Eastern European economies are hurt more by immature tax compliance systems.

By analysing every single tax-related policy recommendation made by the EC over the past five years, we get a nice and clear picture of the nature and trend of European tax politics, both in terms of tax policy paradigms, European countries’ deviation from the consensus, and in terms of the intra-EU games surrounding tax policy analysis.

I want to highlight three key trends in the analysis below:

- Focus on tax compliance, tax shifts and base broadening

- The Commission’s prerogative on tax avoidance and tax havens

- Eastern European tax evasion, French and Italian deviants, and other country trends.

1. Focus on tax compliance, tax shifts and broadening the tax base

Observers of international tax policy probably won’t be surprised by the top EC tax policy recommendations – because it largely aligns with what the EU has been shouting for the past five to ten years. The EU wants national tax systems to strengthen tax compliance, to shift taxation from capital and labour onto consumption and property, and to broaden the tax base.

Heard it before? Yup. Top EU reps repeat it again and again and again. The mission letter by EC President Jean-Claude Juncker to new EU tax commissioner Pierre Moscovici, for instance, reads like a pretty accurate representation of the EU tax-related CSRs:

While recognising the competence of Member States, the modernisation of tax systems is essential for delivering on the priorities of the European Semester of economic policy coordination. Reforms should involve promoting a broadening of the tax base, shifting the tax burden away from labour, improving tax compliance and addressing the debt bias in corporate and personal income taxation. All efforts should also be made to combat tax evasion and tax fraud.

The absolutely most popular tax policy recommendation by the EC is, by far, that countries improve tax compliance and reduce the tax gap. Tax justice campaigners can rest assured their cause is on the agenda. Every fifth EU tax policy recommendation concerns the strengthening of tax law enforcement by tax administrations.

There is good reason for the EU to emphasise the need to strengthen tax compliance. It’s an area that has garnered significant attention in Europe after the crisis, and it has occupied a central place in EU tax policy work over the past few years. This includes EU work on automatic exchange of tax information, VAT fraud, the Code of Conduct on Business Taxation, the revised Parent-Subsidiary Directive, the 4th Anti-Money Laundering Directive, and more. It is simply a high-profile area, where the EU has contributed significantly to policy initiatives, and for which they advocate national support and implementation. No wonder then that it shows up atop the policy recommendations list.

Number two on the list is recommendations for EU Member States to shift the tax burden away from productive factors (labour and capital) onto property, consumption and green taxes. Slightly more than 10% of all EU tax policy recommendations are on this topic.

This is another topic that has been high on the agenda for the EU in the post-crisis era. As a recent Commission working paper on tax shifts notes:

Shifting taxes away from labour to tax bases which are considered least detrimental to growth remains a common policy recommendation from the European Commission and other international institutions.

A cornerstone of the current paradigm in international taxation, the EC and the OECD are touting the benefits of defined tax shifts at every opportunity. In tax economics and policy circles today, it is simply accepted wisdom that corporate and personal taxes are most detrimental to growth, whereas property and consumption taxes are less harmful. Thus, it makes perfect sense for the EU to keep pushing this wisdom as part of its national tax policy recommendations.

Broadening the tax base is the third top recurring policy recommendation. A total of fifteen policy proposals concerned base-broadening (with a peculiar spike of eight recommendations in 2014 alone). It’s another familiar EU tax policy area. Alongside reducing the burden on labour (which is highlighted in the tax shift recommendations noted above, as well as through proposals to reduce the tax wedge) and fighting tax evasion, base-broadening is the third leg in the European Commission’s “smart taxation” strategy. And as mentioned in the introduction, the “broad base, low rates” mantra is clearly an EC priority, with base-broadening a popular proposal and tax reductions (in particular on labour and low-income earners) adding the low rates element.

The full lists and counts of CSRs based on the tax policy subject and policy recommendation is shown below:

2. The Commissions’ prerogative on tax avoidance and tax havens

While the top recommendations align closely EU tax policy work and current policy paradigms, others are surprisingly conspicuous in their absence. Not a single tax policy recommendation concerned tax avoidance, even though the Commission and the Parliament are happy to advertise massive numbers lost by European public coffers. There was no mention of customs procedures and cooperation. Nada on the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB), which the Commission has been working on since 2011. Nothing on the Financial Transactions Tax (FTT), ditto on tax havens. These are not trivial policy areas; they are all priorities for the European Commission and the Union more broadly, yet there is no trace of them in the CSRs.

But why would the Union not make any recommendations over five years on some of its key tax policy priorities? The answer, to me, seems straightforward: To discourage Member States from taking unilateral action. From a Brussels point of view, the issues of (corporate) tax avoidance, tax havens and FTT are international problems calling for international fixes. Thus, the Commission would not want to propose country-specific action. Rather, they want to be in the driver’s seat and lead towards European solutions. The CCCTB’s international nature and policy process, the EU Anti-Tax Avoidance Package and its upcoming tax haven blacklist are good illustrations of this.

3. National trends: Eastern Europe, France, Italy and others

Beyond the in-/exclusion of certain tax policy topics in the country-specific recommendations, the distribution of policy proposals across geographical and economic divides is another valuable point of analysis. It is clear that certain countries are more likely to receive certain recommendations. For instance, as noted above, proposals to improve tax compliance were largely aimed at Eastern European economies.

This is interesting because it shows us the extent of as well as how national economies deviate from current tax policy paradigms, as seen from Brussels.

To gauge these differences between country groups, I applied EU country clusters generated by my colleague Mikkel Mondrup Pedersen based on Whitley’s business systems framework from a 13-year longitudinal study of national institutional indicators in 30 OECD countries. However, as this grouping covers only two-thirds of the EU Member States in my data, I added another cluster (Eastern Europe) to widen the coverage.

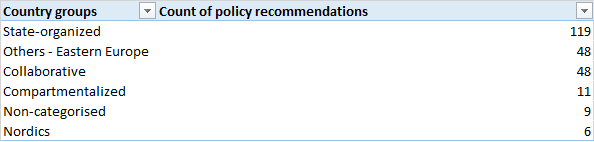

In terms of the overall number of tax policy proposals, the Commission finds most issues with the state-organized economies (119 recommendations), followed by the collaborative business systems (48), Eastern Europe (48), the compartmentalized business systems (11) and the Nordics (six). (To be clear, this is not just because this order reflects the number of countries in each group – the number of recommendations per country number within a group is in the same order). It is clear that the state-organized economies (in particular France and Italy) – with significant state and involvement in the economy and often extensive, complicated tax systems – and Eastern European countries are perceived as deviating mostly from Brussels’ ideal tax system, while the Nordic tax systems are EU favourites.

What about specifics? Which (groups of) countries have received certain tax policy recommendations? Let me list some of the other interesting trends, as seen from the Commission’s point of view:

- All groups of economies needs to reduce the tax wedge, shift the tax burden away from labour, and enhance the environmental friendliness of their tax systems – except the Nordics.

- Outside of tax gap reduction, the main issues for state-organized economies, where the state is highly involved in directing the economy and trade unions are relatively weak, are to reduce tax expenditures and shift tax away from labour.

- Tax compliance proposals are heavily targeted at Eastern Europe (70% of such CSRs). In fact, tax compliance accounts for half of all Eastern European CSRs.

- Tax base broadening proposals are almost exclusively aimed at Europe’s top economies (the G5).

- Germany really needs to improve its tax administration services, having received a recommendation to that effect every year since 2014.

- France really needs to simplify its tax system and reduce inefficient tax expenditures. The French received a policy proposal on tax expenditures every year for the past five years.

- The Netherlands and Sweden are pretty much the only ones who need to reduce debt bias for property investments. (As a Dane, I’m surprised that Denmark has not received this proposal, given that we have one of the highest property-related private debt rates in the world).

These are some of my top takeaways from looking at the EU tax policy recommendations over the past five years. In particular, we clearly see the deliberate spread of a tax policy paradigm concerned with tax compliance, tax shifts and base-broadening. This is likely to continue and EU Member States are likely to converge to these policy agendas in the future. We also see EU institutions looking to control international tax agendas on tax avoidance and tax havens. The European Commission is increasingly working to gain position as a top international institution in tax matters, and this is another mechanism for it to build towards that aspiration. And finally, we see some interesting trends with certain recommendations often targeted at specific (groups) of EU Member States. France, Italy and Eastern European countries are, in particular, being disciplined to conform to the consensus model.

The full data set is available here for your scrutiny. I encourage anyone to dig through the data and I am very happy to hear your comments, suggestions and additions to the approach and the analysis!

4 responses to “Five years of EU tax policy recommendations: Key trends in European taxation”

Interesting overview of EU tax policies versus the States provided by this data – thanks.

[…] in respect of tax matters (see here for a nice synopsis on EU tax policy over the last 5 years by FairSkat). Soft-laws however become much more rigid when the Commission can additionally put some weight […]

[…] tax capital, and instead tax immobile factors (consumption, land and to a lesser extent labour), as my blog on European tax policy plainly shows. Thus, the most popular current streams in addressing tax competition to accept this […]

[…] Blog […]